This weekend the Disney live-action remake of the 1991 Disney animation classic “Beauty and the Beast” made a big splash with audiences, critics, and, especially, the box office. I saw it Friday and was completely enchanted. The movie smartly recreates in live action all that is beloved about the original, with eye-poppingly baroque visual effects, good writing and fine acting, while adding just enough winning new material and occasionally cleverly tweaking the familiar beats too.

The one tweak that got my attention so much I decided to write about it here comes in the new rendition of the title song “Beauty and the Beast”. Emma Thompson steps out of the formidable shadow of the beloved Angela Lansbury to essay her own lovely vocals as Mrs. Potts, the singing teapot. But unlike Angela Lansbury, Emma Thompson finds herself having to smoothly glide through some tricky rhythmic obstacles. Listen and hear for yourself:

Beauty and the Beast – Emma Thompson (music: Alan Mencken; lyrics: Howard Ashman)

At the 1:01 mark this “Beauty and the Beast” turns into a waltz, in 3/4 time, something that didn’t happen in the original.

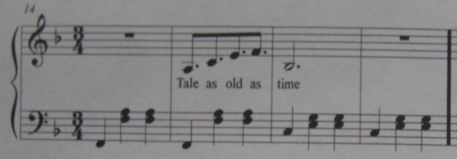

In the original we see Belle and Beast dancing a waltz while Angela Lansbury sings about the tale as old as time, but the music nonetheless remains steadfast in common time, 1 2 3 4, 1 2 3 4… and the melody continues the rhythmic pattern set forth at the beginning of the song and followed through to the end, a phrase of four eighth notes followed by a longer note

In the original we see Belle and Beast dancing a waltz while Angela Lansbury sings about the tale as old as time, but the music nonetheless remains steadfast in common time, 1 2 3 4, 1 2 3 4… and the melody continues the rhythmic pattern set forth at the beginning of the song and followed through to the end, a phrase of four eighth notes followed by a longer note  (Tale as old as time — Beauty and the Beast — da da da da daah — etc.)

(Tale as old as time — Beauty and the Beast — da da da da daah — etc.)

It appears that for the remake the decision was made that when Belle and Beast start dancing their famous waltz the music should join them in 3/4 time; and so it now does, subtly but definitely at the 1:01 minute mark in the recording, staying in 3/4 until the 2:34 minute mark. But how does that change the melody of the song? Is it rhythmically rewritten to accommodate the new time signature? Nope.

Emma Thompson keeps singing the song as if she was singing regular phrases of 4 eighth notes starting on a downbeat and followed by a long final note on the next downbeat. If anything, she holds onto that steady 4 note phrase more rhythmically evenly now than she does during the first minute, where she sings those phrases more freely. In holding on to the steady 4 while underneath her the orchestra is playing a constant 3, Emma Thompson is proving herself the master of a very tricky tuplet.

Tuplet?

What the heck is a tuplet?

Well, have you heard of a triplet? No, not one of three identical babies; in music a triplet is a series of three notes played rhythmically identically where normally there would be just two notes of their kind. The most common triplets are in classical music, 3 eighth notes shortened and crammed into a space where two regular eighths would fit.  Beethoven in particular loved triplets. To the right is one example of triplets played by the right hand in his Pathetique Sonata.

Beethoven in particular loved triplets. To the right is one example of triplets played by the right hand in his Pathetique Sonata.

But popular music has its share of triplets too. Just look at excerpts from the Star Wars main theme….

or Bon Jovi’s “Living on a Prayer”….

But bracketing notes in groups of equal value contrary to the parameters of a piece of music’s regular rhythm does not just come in threes a la triplets. It can come in all varieties of number grouping, hence the family name of tuplet.

Back to “Beauty and the Beast”. I have no access to the music scores the arrangers and singers were using when they recorded this new version of the song, but if I had to make a bet, my guess is what we hear Emma Thompson sing after the 1:01 minute mark would be written out to look much like this:

Which is a tuplet in 4 over a 3/4 waltz rhythm. That is how one would write it out. A bracket over the notes in question with a 4 indicating what normally are three quarter notes are now four notes of equal rhythm fitting within a 3/4 time frame.

One doesn’t have to use tuplets. One could write such a thing out like this:

or like this:

Those alternatives are as rhythmically accurate in this case as using the tuplet, but not as visually simple to grasp.

Now, like I’ve said, I didn’t see how the people at Disney wrote out this arrangement, and it is possible that the scoring of the song didn’t switch to 3/4 time, but simply put waltz emulating triplets in the accompaniment:

But considering the complexity of the orchestral arrangement in the recording (those left hand figures in my score examples are more for show than accurate transcriptions, just the most simple, most obvious waltz accompaniment figures out there), I believe it makes the most sense to assume the arrangers changed time signatures to 3/4 at the 1:01 minute mark of the score and asked the singer to read tuplets in 4. And, as mentioned before, Emma Thompson holds on to those tuplets with a steadiness and seeming ease that belies the distracting 3/4 flourishes undulating underneath her vocal line. Only twice does she “adjust” against the tuplet, starting on the second beat and singing regular eighth notes on “Ever as before” and stretching out the notes Streisand-like on “As the sun will rise”.

Why do I care so much about triplets and tuplets? As a composer these kind of musical details hold a lot of fascination for me. But also as a kid with ten years of piano lessons I had more than a typical musician’s experience with them. Although most musicians will play or sing at least some triplets now or then, piano players are some of the very few who will be required to play the triplet (or tuplet) with one hand, while keeping the regular rhythm steady with the other hand. That is not something we humans do automatically. Just try tapping your feet in a steady 1,2, 1,2 while simultaneously clapping your hands in a steady 1,2,3, 1,2,3 (the 1s of feet and hands always falling at the same moment). Once you mastered that, try it with the left hand in opposition with the right hand. Then try alternating two fingers in the left hand while alternating three fingers in the right hand, and not just for a moment but for a continuous run, as in this section of Beethoven’s Sonata Opus 14 No. 2 (devilishly hard to play well, but once you do, so much fun!):

Not surprisingly I’ve used tuplets, especially triplets, in my music too. A long run of triplets in the vocal line, over a driving 4/8 rhythm is featured twice in the Speakeasy song “Shadow and Light” (you can hear them begin at the 0:49 and 2:18 marks in the demo recording):

Not surprisingly I’ve used tuplets, especially triplets, in my music too. A long run of triplets in the vocal line, over a driving 4/8 rhythm is featured twice in the Speakeasy song “Shadow and Light” (you can hear them begin at the 0:49 and 2:18 marks in the demo recording):

Examples for triplets can be found near and far. Beethoven may have arguably loved using them in opposition to a 2 beat rhythm the most, but he was and is by far not alone. However, using tuplets in 4 against 3/4 time, as demonstrated in this new version of “Beauty and the Beast” is a much rarer thing. I encountered that particular method of rhythmic opposition the first time when I first listened closely to Supertramp’s “Crime of the Century”.

During the extended instrumental that closes the song, the piano plays a distinctive pattern in 3/4 time. The piano is joined by a string section eventually playing a 4 note pattern (starting at the 3:29 mark), descending in starting pitch with each repetition. The 4 note pattern consists of dotted quarter notes (held as long as three eighths), two fitting perfectly rhythmically within each 3/4 measure. But suddenly at the 4:03 mark the strings double time the pattern and tuplets in 4 start descending the scale against the 3/4 rhythm, a feat that is repeated again in the end during the song’s fade out. 4 against 3! For 16 continuous measures! At the time (I was maybe 11 years old) I didn’t know the word tuplet, or how exactly those notes might have been written out for the string players, but I did know I loved what I was hearing, and practiced playing my own imaginary 4 note phrase against a steady 3/4 beat.

During the extended instrumental that closes the song, the piano plays a distinctive pattern in 3/4 time. The piano is joined by a string section eventually playing a 4 note pattern (starting at the 3:29 mark), descending in starting pitch with each repetition. The 4 note pattern consists of dotted quarter notes (held as long as three eighths), two fitting perfectly rhythmically within each 3/4 measure. But suddenly at the 4:03 mark the strings double time the pattern and tuplets in 4 start descending the scale against the 3/4 rhythm, a feat that is repeated again in the end during the song’s fade out. 4 against 3! For 16 continuous measures! At the time (I was maybe 11 years old) I didn’t know the word tuplet, or how exactly those notes might have been written out for the string players, but I did know I loved what I was hearing, and practiced playing my own imaginary 4 note phrase against a steady 3/4 beat.

I was hooked.

Crime of the Century – Supertramp

So fun!

LikeLiked by 1 person