The Metropolitan Opera at Lincoln Center

Friday night Ed and I attended the Met Opera performance of Beethoven’s one and only opera “Fidelio”, and it was glorious. I generally don’t cry at operas, but I did so twice this time, uncontrollably sobbing at the soul piercing beauty of music marvelously performed in crucial dramatic moments.

But I am not here to give a review of the production (look here for that). I am here to muse on a more trivial matter that amused my train of thought on the subway ride home.

Is Fidelio the original honeypot?

As in the “honeypot” employed by spies: “a sexual or romantic relationship created by a covert agent to compromise a target”.

We’ve seen the trope in real life, as in the Prufomo affair or Willy Brandt’s personal assistant / GDR spy (though that wasn’t a romantic relationship, it was a close personal one between West Germany’s unwitting leader and an Eastern Bloc spy). And we’ve seen it in countless spy movies, including the James Bond series of course – every second “Bond girl” is secretly in cahoots with the villain, at least initially, or Bond himself is honey-potting her to get to the villain.

The most devastating honeypot story lines unfolded on the brilliant spy series “The Americans”, where our anti-heroes Keri Russel or Mathew Rhys form romantic relationships with unwitting innocents to gain access important to their secret agent missions. The psychological damage this ultimately wreaks on their victims as well as themselves is brilliantly rendered over several seasons.

Am I seriously comparing Fidelio to the cunning Soviet spies of “The Americans”? Isn’t that a bit much, a bit silly? Well, yes, yes and yes, but it’s also true. One can make a good case that Fidelio is the original Honeypot in fictional drama.

You see, in case you don’t know the opera’s plot, Fidelio is not the young man he is believed to be by the prison warden Rocco and his daughter Marzelline, but actually Leonore, the wife of political prisoner Florestan. At the opera’s start Leonore has infiltrated the prison grounds to work as an apprentice to Rocco in the guise of young Fidelio. Moreover Leonore has taken advantage of Marzelline’s affection for Fidelio – in spite of her being wooed by the callow Jacquino – to win Rocco’s trust, going so far as to agreeing to an engagement with Marzelline.

If you didn’t know Fidelio’s true identity going into the opera, the libretto would have kept you in the dark until late into Act One, when Fidelio/Leonore sings about her intentions to find her husband languishing in a secret dungeon cell in the depths of the prison only Rocco has access to. After all, Fidelio being sung by a woman would not have been any clue that Fidelio really is a woman in disguise, since operas in Beethoven’s time regularly employed “pants roles”, young male characters performed by female singers.

Before Leonore’s big act one aria, you might think you are attending a light comic opera about a love triangle. Jacquino adores Marzelline, but she pines for Fidelio, who reciprocates. The only hint, at first, that something is off is during a famously stirring quartet shared by Fidelio, Marzelline, Rocco and Jacquino: after Marzelline sings (I’m paraphrasing) “oh what joy”, Fidelio sings “oh what danger” on the same melodic line. Danger? Why? Only in small moments and phrases is the truth about Fidelio’s subterfuge hinted at before the late-in-the-act bravura aria, when Leonore unburdens her soul and reveals her intentions.

Lise Davidson as Fidelio/Leonore; René Pape as Rocco; Ying Fang as Marzelline

With that the opera moves into heavier themes and drama, leaving the romantic comedy plot behind. In the end, the despot is overthrown and Florestan and all other prisoners released. Leonore and Florestan are united, and – at least as far as the libretto seems concerned – Marzelline is left to be content with Jacquino. In previous productions I’ve seen of “Fidelio” that turn of events is played lightly and conveniently.

But in this production at the Met, Marzelline’s realization of Fidelio’s true identity is staged for full effect, as she approaches him/her with a bouquet of red roses, half of which she then open-mouthedly drops in shocked recognition. That gets a laugh in the moment. But as the (musically ecstatic) celebration of freedom and justice by the townsfolk and released prisoners continues, Marzelline is left singing along but still clearly shell-shocked and distraught, continually dropping rose stems while embraced from behind by the jubilant Jaquino, who seems cognizant only of his romantic triumph, not his beloved’s despair.

Similarly Leonore appears to pay Marzelline little heed, engrossed as she and Florestan are with each other and her heroism. There is still an element of humor in the pitiful display of Marzelline’s shock and anguish during this celebratory climax, as rousing as the “Ode to Joy” is in Beethoven’s Ninth, but by committing to Marzelline’s despair throughout both the production and performer add a sting to the proceedings, reminding us of the emotional and personal collateral damage of Leonore’s heroism.

And in doing so highlights the psychological gamesmanship Leonore had been engaged in while she infiltrated the prison and Rocco’s family. Just like the most crafty spy out of any secret agent thriller. The original Honeypot.

The text on the scrim reads “Wahre Liebe fürchtet nicht.” – “True Love fears not.”

Bonus Feature: Views in the Family Circle

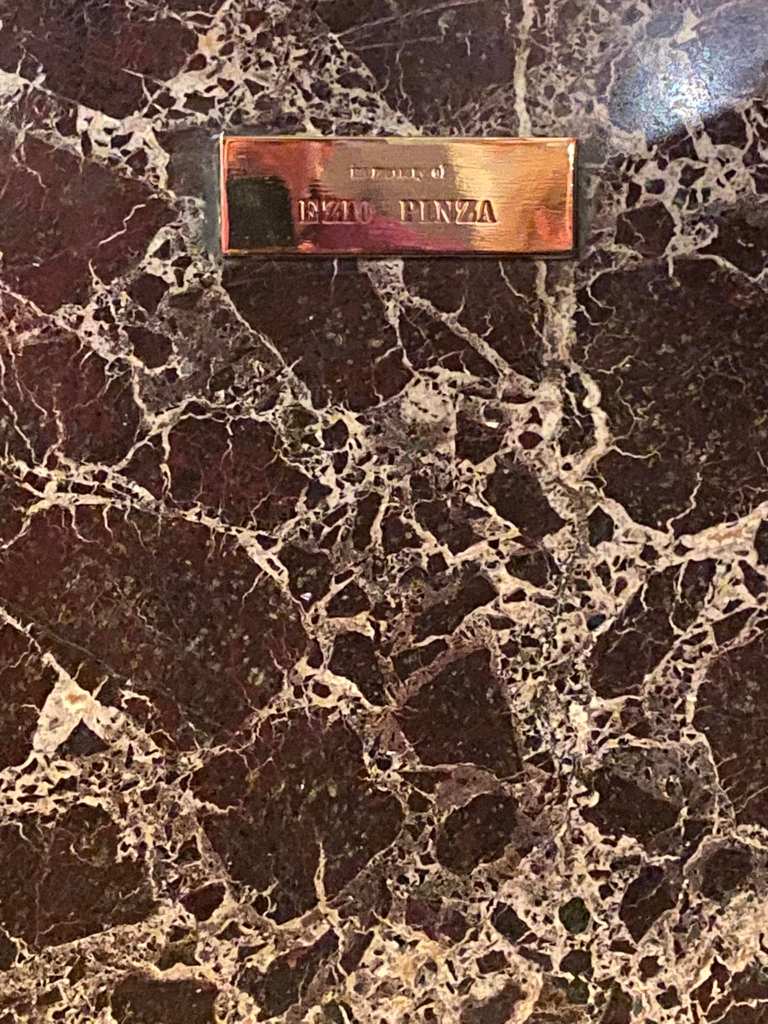

The water fountain is in memory of Ezio Pinza