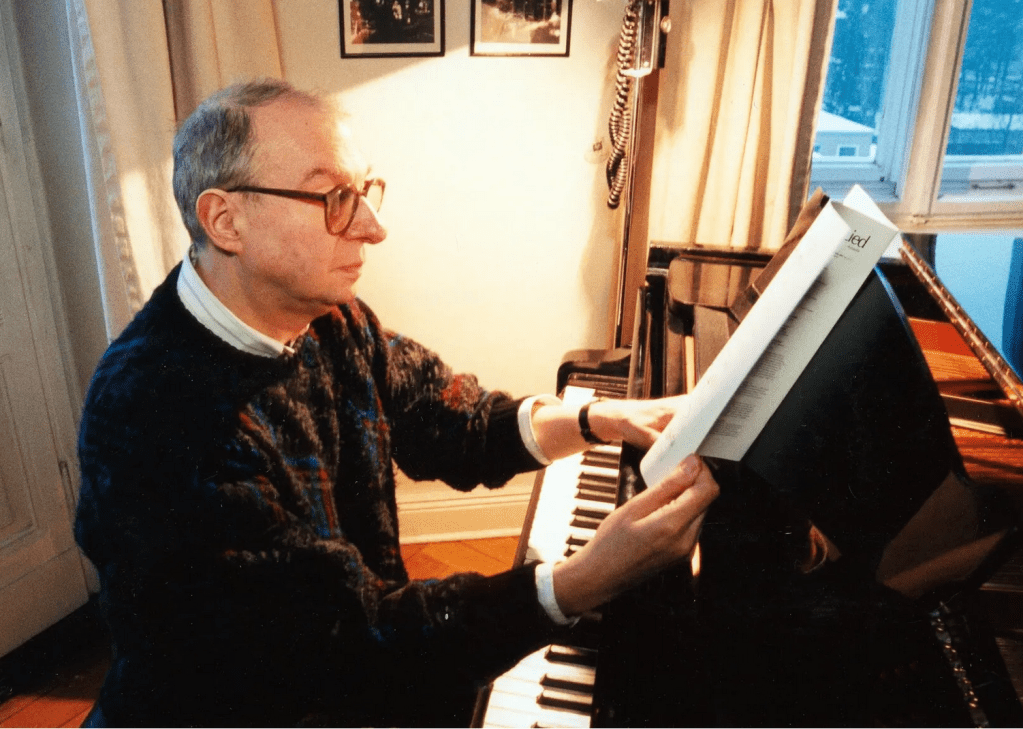

Aribert Reimann with my mother, Catherine Gayer, at rehearsal in 1971

Two Thursdays ago my mother called me from Berlin. Normally we talk on Sundays, so I was curious what occasioned this call.

“Aribert Reimann has died”, she told me, with shock in her voice. Aribert was a friend and colleague and contemporary, just a year older than Mom.

He was also one of the great composers of contemporary music. The New York Times obituary – which I will share below – refers to his many well received operas, specifically his widely produced setting of Shakespeare’s King Lear.

My Mom, Catherine Gayer (her maiden name being her stage name), worked countless times with Aribert Reimann. They performed many recitals together – he was also an accomplished pianist – and he composed many pieces for her to sing, including the lead in his second opera (also mentioned in the NYTimes obit) “Melusine”.

Performed in 1971, the Guardian at the time described the musical language of “Melusine” as neo-expresionist, with writing for voices in declamatory style and with demanding coloraturas.

Breezily executing demanding coloraturas was my mother’s bread and butter. Reimann was not the only contemporary composer who took advantage of her ability to sing difficult modern vocal writing with aplomb. But he composed more for her than all the others.

Mom, kneeling, as Melusine, with Martha Mödl behind her.

YouTube has the complete song cycle “6 Poems by Sylvia Plath” Reimann composed for Mom to sing. I’ll share the first piece here, but all 6 as well as both parts of “Nachtstücke” are accessible.

YouTube also has – in two parts – the recording of a recital Reimann and Mom performed in 1973. I’ll start you off with the first part here:

Although I saw my mother and Aribert Reimann work together again and again throughout my childhood, I didn’t have much of a relationship with him myself. The one anecdote I can think of is going with my parents to a party at his home, when I was around 14 years old. In 1981 or 1982.

He wasn’t the first of whom I knew at the time that he was homosexual, but I believe this was the first time I was knowingly in the home of a partnered homosexual. I was the only teenager there – my parents often took me along to parties and gatherings where everyone else was an adult – and I started wandering around the very large pre-war Berlin apartment.

I was particularly taken by some overtly homoerotic art or photography, and was seen staring at it by Aribert’s boyfriend. I felt caught as he looked the other way.

Not much of a story perhaps, but an indelible memory nonetheless.

Here is the obituary from the New York Times:

Aribert Reimann, Masterful German Opera Composer, Is Dead at 88

His works, which were radically individual, were among the most celebrated of the late 20th and early 21st century.

A.J. Goldmann is an American journalist who writes about European arts and culture. He is based in Munich.

Published March 19, 2024 – Updated March 22, 2024

“Aribert Reimann, whose powerful operas based on works by Shakespeare, Kafka, Lorca and others made him one of the most significant opera composers of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, died on Wednesday in Berlin. He was 88.

His publisher, Schott Music, announced the death.

A prolific composer whose works were widely performed, particularly his operas and songs, Mr. Reimann (pronounced RYE-mahn) was revered for his ability to fuse complex and often challenging modern music with lyrical texts. His works were frequently devastating in their emotional impact, sounding like organic expressions of the human voice.

“Like few other composers of his generation, Reimann knew how to tell stories in his operas which directly affected us humans living in the 21st century,” Dietmar Schwarz, the manager of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, said in a statement.

Mr. Reimann enjoyed a close relationship with that opera house. Five of his stage works were performed there, most recently his ninth and final completed opera, “L’Invisible,” based on texts by the Belgian Symbolist Maurice Maeterlinck, which premiered in 2017.

Another stage work, based on Oscar Wilde’s “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” was planned for 2025 but was unfinished.

Mr. Reimann used serial-music principles, though not rigidly; his catalog of more than 130 compositions included many pieces free of traditional beat and meter. The result was a musical language that sounded at once brazenly contemporary, archaic and timeless — a powerful conduit for drama and extreme emotions.

He wrote a requiem in 1982, several concertos and assorted chamber pieces, but only one symphony. He was a professor of contemporary lieder, or German art song, at the Hochschule für Musik in Hamburg and the Hochschule der Künste, now the Universität der Künste, or University of the Arts, in Berlin.

His best-known opera, “Lear,” based on Shakespeare’s tragedy, debuted in 1978 in Munich at the Bayerische Staatsoper, or Bavarian State Opera; three years later, it had its United States premiere in San Francisco. Since then there have been more than 30 productions of the work, despite its being less than 50 years old.

The thunderous title role, which Mr. Reimann wrote for the German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, a frequent collaborator, is noted for its musical difficulty. Its climax is the shattering aria “Weint! Weint! Weint! Weint!” (“Howl! Howl! Howl! Howl!”), a cantorial threnody mourning Lear’s daughter Cordelia. Contemporary singers, including Gerald Finley and Christian Gerhaher, have been drawn to the role for its musical and expressive challenges.

Aribert Reimann was born into a musical family in Berlin on March 4, 1936, when the Nazis held power. His father, Wolfgang Reimann, was an organist and director of the Berlin State and Cathedral Choir. His mother, Irmgard Rühle, was an alto and a singing teacher. A brother five years his senior was killed in an Allied bombing raid in March 1944.

“After the war, we spent four months on the road as refugees, pushing our belongings in a cart, like Mother Courage,” Mr. Reimann said in a 2021 interview for Deutsche Oper Berlin. “I was 9. The only thing we had to survive on was a box of Knorr stock cubes.”

After the war, Mr. Reimann grew up in the Zehlendorf section of what was then West Berlin. At 10, he had a formative experience that would set him on the path to composing: singing a primary role in a production of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s opera “Der Jasager.”

“The encounter with Weill’s music, which I had never heard before because it was not allowed to be played in the Third Reich, was absolutely overwhelming for me because it opened up a tonal but completely new sound world,” Mr. Reimann said in a 2018 interview for his former secondary school’s annual publication.

He also began composing short works for piano at 10. Shortly after, he accompanied his mother’s vocal students at concerts.

In 1955, after graduating from high school, he worked at the newly founded opera studio of the Städtische Oper Berlin, now the Deutsche Oper, while taking composition and piano classes at the city’s music conservatory. He also briefly studied musicology at the University of Vienna.

One of his professors at the Berlin conservatory was the influential German composer Boris Blacher, who advised Mr. Reimann to avoid the avant-garde hubs of Darmstadt and Donaueschingen — incubators of modern music with reputations for being experimental but dogmatic — and instead to forge his own path. Doing so, he distinguished himself from older contemporaries, like Karlheinz Stockhausen and Hans Werner Henze, and throughout his long career he remained radically individual, even solitary, as an artist who never belonged to any musical movement or school.

Starting in his 20s, Mr. Reimann accompanied Mr. Fischer-Dieskau and the mezzo-soprano Brigitte Fassbaender in recitals and wrote music for them. Throughout his career he remained a sought-after and frequently recorded accompanist, and he championed young composers through the establishment of the Busoni Composition Prize in 1988 and the Aribert Reimann Foundation, which was founded in 2006.

In 1962, his concert piece “Fünf Gedichte von Paul Celan,” or “Five Poems by Paul Celan,” premiered at the Berliner Festwochen, an annual performing arts festival, with Mr. Fischer-Dieskau as soloist. Mr. Reimann had met Mr. Celan, a Jewish Romanian poet who had survived the Holocaust, in Paris in 1957, and was among the first to set his haunting German-language poems to music. Mr. Reimann returned to Mr. Celan’s poetry in 1971, a year after the writer died by suicide, for “Zyklus,” a setting of six poems in a single movement of about 20 minutes.

“The printed score looks forbidding, with its unconventional, up‐to‐the‐minute notation,” Harold C. Schonberg of The New York Times wrote in his review of the work’s U.S. premiere in 1974. “But, as sometimes happens, the actual sounds are less forbidding than one might suspect.” Mr. Reimann, Mr. Schonberg noted, had “largely discarded the abstract austerities” of the previous two decades.

In 1963, Mr. Reimann began composing his first opera, “Ein Traumspiel,” based on “A Dream Play,” by August Strindberg. It debuted two years later in Kiel. “Melusine,” based on a play by the French-German poet Yvan Goll, followed in 1971. He also collaborated with Günter Grass — who went on to win a Nobel Prize in Literature — on two ballets.

Mr. Reimann, who was gay, was not married at his death and had no children. Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

Many of his operas after “Lear” featured female protagonists, including “Troades” (1986), an adaptation of Euripides’ “The Trojan Women.”

In various interviews about “Medea,” which premiered at the Vienna State Opera to great acclaim in 2010, Mr. Reimann said that he found the titular figure, a migrant woman who is deprived of her rights in her new homeland, to be extremely timely.

“My art will never just be about personal stuff,” he said in the 2021 Deutsche Oper interview. “I can’t set material to music if it doesn’t have some measure of social relevance.”